How immigrants can obtain health coverage

Key takeaways

- Immigrants can enroll in individual health plans during open enrollment period, just like any other lawfully present U.S. resident.

- Lawfully present immigrants – including those in the U.S. temporarily on work or student visas – are eligible for premium subsidies.

- There’s a special enrollment period for new citizens and new lawfully present residents.

- Recent immigrants with income below the poverty level are eligible for subsidies in the exchange.

- Health plans (and subsidies) are available in the individual market for recent immigrants age 65+.

- Undocumented immigrants cannot buy plans in the exchange, but some states provide coverage for some undocumented immigrant children and pregnant women.

- When you apply for a plan in the exchange, you may need to prove your immigration status.

- Short-term health plans are an alternative for recent immigrants who can’t afford an ACA-compliant plan.

- California abandoned its efforts to allow undocumented immigrants to buy full-price plans in the exchange, and New York legislation did not advance.

- Trump administration’s “public charge” rule and immigrant visa insurance requirements: Both rules have been blocked by the courts, but an appeals court has stayed the vacating of the public charge rule, so it can still be implemented in some states, and an appeals court has vacated the injunction that had blocked the health coverage requirements for immigrants.

Did the ACA improve access to health coverage for immigrants?

For more than a decade, roughly one million people per year have been granted lawful permanent residence in the United States. In addition, there are about 11 million undocumented immigrants in the U.S, although that number has fallen from a high of more than 12 million in 2005.

New immigrants can obtain health insurance from a variety of sources, including employer-sponsored plans, the individual market, and health plans that are marketed specifically for immigrants.

The Affordable Care Act has made numerous changes to our health insurance system over the last several years. But recent immigrants are often confused in terms of what health insurance options are available to them. And persistent myths about the ACA have made it hard to discern what’s true and what’s not in terms of how the ACA applies to immigrants.

So let’s take a look at the health insurance options for immigrants, and how they’ve changed – or haven’t changed – under the ACA.

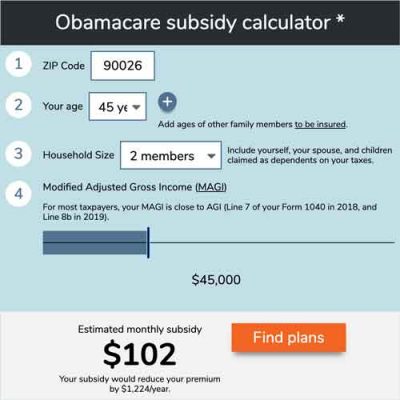

Use our calculator to estimate how much you could save on your ACA-compliant health insurance premiums.

Can any immigrant select from available health plans during open enrollment?

Open enrollment for individual-market health insurance coverage runs from November 1 to December 15 in most states.

During this window, any non-incarcerated, lawfully present U.S. resident can enroll in a health plan through the exchange in their state – or outside the exchange, if that’s their preference, although financial assistance is not available outside the exchange.

Are immigrants eligible for health insurance premium subsidies?

You do not have to be a U.S. citizen to benefit from the ACA. If you’re in the U.S. legally – regardless of how long you’ve been here – you’re eligible for subsidies in the exchange if your income is in the subsidy-eligible range and you don’t have access to an affordable, minimum value plan from an employer. Premium subsidies are available to exchange enrollees if their income is between 100 percent and 400 percent of the federal poverty level (FPL), but subsidies also extend below the poverty level for recent immigrants, as described below.

(A new rule issued by the Trump administration in 2019 expanded on the long-standing “public charge” rule. This rule took effect in early 2020. It was vacated by a federal judge as of November 2020, but that order was stayed by an appeals court just two days later, meaning that the Trump administration’s public charge rule can still be implemented while litigation continues on this case. Under the public charge rule, receiving premium subsidies in the exchange does not make a person a public charge under the new rule, but not receiving premium subsidies is considered a “heavily weighted positive factor” in the overall determination of whether a person is likely to be a public charge. This is discussed in more detail below.)

Lawfully present immigrant status applies to a wide range of people, including those with “non-immigrant” status such as work visas and student visas. So even if you’re only in the U.S. temporarily — for a year of studying abroad, for example — you can purchase coverage in the health insurance exchange for the state you’re living in while in the US. And depending on your income, you might be eligible for a premium subsidy to offset some of the cost of the coverage.

Special enrollment period for new citizens

When you become a new U.S. citizen or gain lawfully present status, you’re entitled to a special enrollment period in your state’s exchange. You’ll have 60 days from the date you became a citizen or a lawfully present resident to enroll in a plan through the exchange, with subsidies if you’re eligible for them.

There are a variety of other special enrollment periods that apply to people experiencing various qualifying life events. These special enrollment periods are available to immigrants and non-immigrants alike.

Are recent immigrants eligible for ACA subsidies?

The ACA called for expansion of Medicaid to all adults with income up to 138 percent of the poverty level, and no exchange subsidies for enrollees with income below the poverty level, since they’re supposed to have Medicaid instead. But Medicaid isn’t available in most states to recent immigrants until they’ve been lawfully present in the U.S. for five years. To get around this problem, Congress included a provision in the ACA to allow recent immigrants to get subsidies in the exchange regardless of how low their income is.

Low-income, lawfully present immigrants – who would be eligible for Medicaid based on income, but are barred from Medicaid because of their immigration status – are eligible to enroll in plans through the exchange with full subsidies during the five years when Medicaid is not available. Their premiums for the second-lowest-cost Silver plan are capped at 2.07 percent of income in 2021 (this number changes slightly each year).

In early 2015, Andrew Sprung explained that this provision of the ACA wasn’t well understood during the first open enrollment period, even by call center staff. So there may well have been low-income immigrants who didn’t end up enrolling due to miscommunication. But this issue is now likely to be much better understood by exchange staff, brokers, and enrollment assisters. If you’re in this situation and are told that you can’t get subsidies, don’t give up — ask to speak with a supervisor who can help you (for reference, this issue is detailed in ACA Section 1401(c)(1)(B), and it appears on page 113 of the text of the ACA).

Lawmakers included subsidies for low-income immigrants who weren’t eligible for Medicaid specifically to avoid a coverage gap. Ironically, there are currently about 2.3 million people in 13 states who are in a coverage gap that exists because those states have refused to expand Medicaid (two of those states — Missouri and Oklahoma — will expand Medicaid as of mid-2021, and Georgia will partially expand Medicaid, eliminating the coverage gap; at that point, there will only be 10 states with coverage gaps). Congress went out of their way to ensure that there would be no coverage gap for recent immigrants, but they couldn’t anticipate that the Supreme Court would make Medicaid optional for the states and that numerous states would block expansion, leading to a coverage gap for millions of U.S. citizens.

Can recent immigrants 65 and older buy exchange health plans?

Most Americans become eligible for Medicare when they turn 65, and no longer need individual-market coverage. But recent immigrants are not eligible to buy into the Medicare program until they’ve been lawfully present in the U.S. for five years.

Prior to 2014, this presented a conundrum for elderly immigrants, since individual market health insurance generally wasn’t available to anyone over the age of 64. But now that the ACA has been implemented, policies in the individual market are available on a guaranteed-issue basis, regardless of age. And if the plan is purchased in the exchange, subsidies are available based on income, just as they are for younger enrollees. (It’s unlawful to sell an individual market plan to anyone who has Medicare, but recent immigrants cannot enroll in Medicare).

The ACA also limits premiums for older enrollees to three times the premiums charged for younger enrollees. So there are essentially caps on the premiums that apply to elderly recent immigrants who are using the individual market in place of Medicare, even if their income is too high to qualify for subsidies.

Are undocumented immigrants eligible for ACA coverage?

Although the ACA provides benefits to U.S. citizens and lawfully present immigrants alike, it does not directly provide any benefits for undocumented immigrants.

The ACA specifically prevents non-lawfully present immigrants from enrolling in coverage through the exchanges [section 1312(f)(3)]. And they are also not eligible for Medicaid under federal guidelines. So the two major cornerstones of coverage expansion under the ACA are not available to undocumented immigrants.

Some states have implemented programs to cover undocumented immigrants, particularly children and/or pregnant women. For example, Oregon’s Cover All Kids program provides coverage to kids in households with income up to 305 percent of the poverty level, regardless of immigration status. California has had a similar program for children since 2016, and as of 2020, it also applied to young adults through the age of 25. New York covers kids and pregnant women in its Medicaid program regardless of income, and covers emergency care for other undocumented immigrants in certain circumstances.

It’s important to understand that if you’re lawfully present, you can enroll in a plan through the exchange even if some members of your family are not lawfully present. Family members who aren’t applying for coverage are not asked for details about their immigration status. And HealthCare.gov clarifies that immigration details you provide to the exchange during your enrollment and verification process are not shared with any immigration authorities.

How many undocumented immigrants are uninsured?

In terms of the insurance status of undocumented immigrants, the numbers tend to be rough estimates, since exact data regarding undocumented immigrants can be difficult to pin down. But according to Pew Research data, there were 11 million undocumented immigrants in the U.S. as of 2014.

According to a recent Kaiser Family Foundation analysis, undocumented immigrants are significantly more likely to be uninsured than U.S. citizens: 45 percent of undocumented immigrants are uninsured, versus about 8 percent of citizens.

So more than half of the undocumented immigrant population has some form of health insurance coverage. Kaiser Family Foundation’s Larry Levitt noted via Twitter that “some are buying non-group, but I’d agree that it’s primarily employer coverage.” And in 2014, Los Angeles Times writer Lisa Zamosky explained the various options that undocumented immigrants in California were using to obtain coverage, including student health plans, employer-sponsored coverage, and individual (i.e., non-group) plans purchased off-exchange (on-exchange, enrollees are required to provide proof of legal immigration status).

Uninsured undocumented immigrants do have access to some healthcare services, regardless of their ability to pay. Federal law (EMTALA) requires Medicare-participating hospitals to provide screening and stabilization services for anyone who enters their emergency rooms, without regard for insurance or residency status.

Since emergency rooms are the most expensive setting for healthcare, local officials in many areas have opted for less expensive alternatives. Of the 25 U.S counties with the largest number of undocumented immigrants, the Wall Street Journal reports that 20 have programs in place to fund primary and surgical care for low-income uninsured county residents, typically regardless of their immigration status.

Do ACA exchanges check the status of immigrants who want to buy coverage?

As part of the enrollment process, the exchanges are required to verify lawfully present status. In 2014, enrollments were terminated for approximately 109,000 people who had initially enrolled through HealthCare.gov, but who were unable to provide the necessary proof of legal residency (enrollees generally have 95 days to provide documentation to resolve data matching issues for immigration status).

By the end of June 2015, coverage in the federally facilitated exchange had been terminated for roughly 306,000 people who had enrolled in coverage for 2015 but had not provided adequate documentation to prove their lawfully-present status. In the first three months of 2016, coverage in the federally facilitated exchange was terminated for roughly 17,000 people who had unresolved immigration data matching issues, and coverage was terminated for the same reason for another 113,000 enrollees during the second quarter of 2016.

There’s concern among consumer advocates that some lawfully present residents have encountered barriers to enrollment – or canceled coverage – due to data-matching issues. If you’re lawfully present in the U.S (which includes a wide range of immigration statuses), you can legally use the exchange, and qualify for subsidies if you’re otherwise eligible. Be prepared, however, for the possibility that you might have to prove your lawfully present status.

There are enrollment assisters in your community who can help you with this process if necessary. But if you’re not lawfully present, you cannot enroll through the exchange, even if you’re willing to pay full price for your coverage. You can, however, apply for an ACA-compliant plan outside the exchange, as there’s no federal restriction on that.

Should immigrants consider short-term health insurance?

Immigrants who are unable to afford ACA-compliant coverage might find that a short-term health insurance plan will fit their needs, and it’s far better than being uninsured. Short-term plans are not sold through the health insurance exchanges, so the exchange requirement that enrollees provide proof of legal residency does not apply with short-term plans.

Short-term plans provide coverage that’s less comprehensive than ACA-compliant plans, and for the most part, they do not provide any coverage for pre-existing conditions. But for healthy applicants who can qualify for coverage, a short-term plan is far better than no coverage at all. And the premiums for short-term plans are far lower than the unsubsidized premiums for ACA-compliant plans.

Recent immigrants who are eligible for premium subsidies in the exchange will likely be best served by enrolling in a plan through the exchange — the coverage will be comprehensive, with no limits on annual or lifetime benefits and no exclusions for pre-existing conditions. But healthy applicants who aren’t eligible for subsidies (including those affected by the family glitch, and those with income just a little above 400 percent of the poverty level), as well as those who might find it difficult to prove their immigration status to the exchange, may find that a short-term policy is their best option.

Recent immigrants who are eligible for premium subsidies in the exchange will likely be best served by enrolling in a plan through the exchange — the coverage will be comprehensive, with no limits on annual or lifetime benefits and no exclusions for pre-existing conditions. But healthy applicants who aren’t eligible for subsidies (including those affected by the family glitch, and those with income just a little above 400 percent of the poverty level), as well as those who might find it difficult to prove their immigration status to the exchange, may find that a short-term policy is their best option.

With any insurance plan, it’s important to read the fine print and understand the ins and outs of the coverage. But that’s particularly important with short-term plans, as they’re not regulated by federal law (other than the rules that limit their terms to no more than 364 days, and total duration to no more than 36 months including renewals). Some states have extensive rules for short-term plans, so availability varies considerably from one state to another (you can click on a state on this map to see how the state regulates short-term plans).

Travel insurance plans are another option, particularly for people who will be in the U.S. temporarily and who don’t qualify for premium subsidies in the exchange. Just like short-term plans, travel insurance policies are not compliant with the ACA, so they generally won’t cover pre-existing conditions, tend to have gaps in their coverage (since they don’t have to cover all of the essential health benefits) and will come with limits on how much they’ll pay for an enrollee’s medical care. But if the other alternative is to go uninsured, a travel insurance plan is far better than no coverage at all.

How are states making efforts to insure undocumented immigrants?

California wanted to open up its state-run exchange to undocumented immigrants who can pay full price for their coverage. The state already changed the rules to allow for the provision of Medicaid (Medi-Cal) to undocumented immigrant children, starting in 2016 (and expanded this to young adults as of 2020). As a result, about 170,000 children in California gained access to coverage.

And in June 2016, California Governor Jerry Brown signed SB10 into law, setting the stage for the state to eventually allow undocumented immigrants to enroll in coverage (without subsidies) through Covered California, the state-run exchange.

In September 2016, after obtaining public comment on the proposal, Covered California submitted their 1332 Innovation Waiver to CMS, requesting the ability to allow undocumented immigrants to enroll in full-price coverage through Covered California. But in January 2017, just two days before Donald Trump’s inauguration, the state withdrew their waiver proposal, citing concerns that the Trump Administration might use information from Covered California to deport undocumented immigrants.

New York lawmakers considered legislation in 2019 that would have allowed undocumented immigrants to purchase full-price coverage in NY’s state-based exchange, but it did not progress in the legislature. As noted in the text of the legislation, New York would have needed to obtain federal permission to implement this law if the state had enacted it.

Trump administration’s public charge rule and immigrant health insurance rule: Both have been blocked by the courts, but the public charge rule can still be implemented in many states and an appeals court has vacated the injunction that had blocked the immigrant health insurance rule

In August 2019, the Trump administration finalized rule changes for the government’s existing “public charge” policy, after proposing changes nearly a year earlier. And in October 2019, President Trump issued a proclamation to suspend new immigrant visas for people who are unable to prove that they’ll be able to purchase (non-taxpayer funded) health insurance within 30 days of entering the US “unless the alien possesses the financial resources to pay for reasonably foreseeable medical costs.” But both of these rules have since been blocked by federal judges, but subsequent court rulings have relaxed or overturned those earlier actions. The Biden administration is expected to reverse the rule changes in the fairly near future.

The public charge rule was slated to take effect October 15, 2019, but federal judges blocked it on October 11, temporarily delaying implementation. In January 2020, the Supreme Court ruled (in a 5-4 vote) that the public charge rule could take effect while an appeal was pending, and it took effect in February 2020. The Supreme Court declined to temporarily pause the rule amid the COVID pandemic. But U.S. District Judge Gary Feinerman, in Chicago, vacated the rule in its entirety, nationwide, as of November 2020. Just two days later, however, the Seventh Circuit Court of Appeals stayed Judge Feinerman’s order, allowing the Trump administration’s version of the public charge rule to continue to be implemented while litigation on this case continues. On December 2, however, the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals blocked the rule from being applied in 18 states and DC. So as of December 2020, the public charge rule can be used by immigration officials in some states but not in others.

A 2019 Kaiser Family Foundation analysis of the rule indicated that millions of people might disenroll from Medicaid and CHIP (even though CHIP enrollment is not a negatively weighted factor under the new rule) over concerns about the public charge rule, and that “coverage losses also will likely decrease revenues and increase uncompensated care for providers and have spillover effects within communities.”

In addition to the public charge rule being vacated (albeit very temporarily, as the order was soon stayed and the rule is allowed to continue to be implemented for the time being, although not in the states where the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals has blocked it), the health insurance rules for immigrants were also initially blocked by the courts.

In November 2019, the day before the proclamation regarding health coverage for immigrants was to take effect, a 28-day restraining order was issued by District Judge Michael H. Simon. Judge Simon subsequently issued a preliminary injunction, blocking the rule from taking effect. And an appeals court panel upheld the ruling in May 2020. But in December 2020, a three-judge panel from the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit vacated the preliminary injunction, issuing a 2-1 ruling in favor of allowing the Trump administration’s immigrant health insurance requirements to be implemented.

The ruling is not immediately binding, however, and the challengers to the immigrant health insurance rule have 45 days to petition for a rehearing with the full Ninth Circuit. By that point, the Biden administration will be in place, and is expected to reverse the rule, making it unlikely that it will actually be implemented.

Even before they were initially blocked by the courts, the new public charge rule and the new immigrant health insurance requirement did not change anything about eligibility for premium subsidies in the exchange — subsidies continued to be available to legally-present residents who meet the guidelines for subsidy eligibility. But these new rules were designed to make it harder for people to enter the US in the first place, and had the effect of deterring otherwise eligible people from applying for financial assistance with their health coverage, including assistance via Medicaid or CHIP for their US-born children.

Here are more details about both rules:

Public charge rule

The public charge rule was initially delayed for a few months amid legal challenges, but it was implemented in February 2020. It was vacated by a federal judge in November 2020, but that order was soon stayed by the Seventh Circuit Court of Appeals, allowing the Trump administration’s version of the public charge rule to continue to be implemented while litigation on the case continues. Soon thereafter, the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals blocked the rule from being used by immigration officials in 18 states and DC, but it can still be used in the majority of the states.

And advocates note that the rule, which was proposed in 2018, began to lead to coverage losses immediately, even though it didn’t take effect until 2020. The rule has to numerous immigrants forgoing the benefits for which they and their children are eligible, out of fear of being labeled a public charge. Georgetown University’s Health Policy Institute, Center for Children and Families noted this fall that the public charge rule change was one of the factors linked to the sharp increase in the uninsured rate among children in the U.S.

The longstanding public charge rule states that if the government determines that an immigrant is “likely to become a public charge,” that can be a factor in denying the person legal permanent resident (LPR) status and/or entry into the U.S.

For two decades, the rules have excluded Medicaid (except when used to fund long-term care in an institution) from the services that are considered when determining if a person is likely to become a public charge. The new rule changed that: Medicaid, along with Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF), and several low-income housing programs were added to the list of services that would push a person into the “public charge” category. The National Immigration Law Center notes that the public charge assessment does not apply to lawful permanent residents who are renewing their green cards.

Critically, CHIP and ACA premium subsidies are not included among the new additions to the public charge determination, although the final rule does incorporate a “heavily weighted positive factor” that essentially gives the person credit for having private health insurance without using the ACA’s premium subsidies. (In other words, a person’s likelihood of being labeled a public charge will decrease if they have health insurance without premium subsidies, but enrolling in a subsidized plan through the exchange will not count as a negative factor in determining whether the person is likely to become a public charge.)

Very few new immigrants are eligible for Medicaid, due to the five-year waiting period that applies in most cases. But immigrants who have been in the U.S. for more than five years can enroll in Medicaid, and more recent immigrants can enroll their U.S.-born children in Medicaid; these are perfectly legal uses of the Medicaid system. But even before the new rule was scheduled to take effect, it was making immigrants fearful about applying for subsidies, CHIP, or health coverage in general — for themselves as well as for their family members who are U.S. citizens and thus entitled to the same benefits as any other citizen.

Health insurance proclamation for new immigrants

The restraining order for the health insurance proclamation, the subsequent preliminary injunction, and the appeals court panel’s ruling were in response to a lawsuit filed in October 2019, in which plaintiffs argued that the new health insurance rules for immigrants are arbitrary and simply wouldn’t work, given the actual health insurance options available for people who haven’t yet arrived in the US. The court system has, for the time being, blocked the proclamation from taking effect nationwide. And although the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals has vacated the injunction that had been blocking the rule, the Biden administration is expected to overturn the immigrant proclamation soon after taking office.

This Q&A with Immigration attorney William Stock provides some very useful insight into the implications of the health insurance proclamation for new immigrants, if it had been allowed to take effect. The new rules wouldn’t have applied to immigrant visas issued prior to November 3, 2019 (the date the rules were slated to take effect), but people applying to enter the US on an immigrant visa after that date would have had to prove that they have or will imminently obtain health insurance, or that they have the financial means to pay for “reasonably foreseeable medical costs” — which is certainly a very grey area and very much open to interpretation (these rules could take effect at a later date, if and when the proclamation is allowed to take effect).

The rule would not have allowed new immigrants to plan to enroll in a subsidized health insurance plan in the exchange. Premium subsidies would have continued to be available to legally present immigrants, but new immigrants entering the US on an immigrant visa would have had to show that their plan for obtaining health insurance did not involve premium subsidies in the exchange. And applicants cannot enroll in an ACA-compliant plan unless they’re already living in the US, so people trying to move to the US would not have been able to enroll until after they arrive.

There are also concerns about the logistics of getting a plan in place if a person wanted to sign up for a full-price ACA-compliant plan: Gaining lawfully-present immigration status is a qualifying event that allows a person to enroll in a plan through the exchange (but not outside the exchange), but the special enrollment period is not available in advance; it starts when the person gains their immigration status. At that point, the person has 60 days to enroll. If they sign up by the 15th of the month, coverage starts the following month. But if they sign up after the 15th of the month, coverage starts the first of the second following month, which might be more than 30 days after the person arrives in the country. In short, the requirements of the proclamation don’t necessarily match up with the logistics of how enrollment works in the ACA-compliant market.

Under the terms of the proclamation, short-term health insurance plans would have been considered an acceptable alternative for new immigrants. But short-term plans often have a requirement that non-US-citizens have resided in the US for a certain amount of time prior to enrolling, which would make them unavailable for people living outside the US who are applying for an immigrant visa. A travel/expat policy (which has a limited duration, just like short-term coverage) would be available in these scenarios, however, and can be readily obtained by healthy people who are going to be living or traveling outside of their country of citizenship.

Under a Democratic administration, would health insurance assistance for immigrants expand?

The Medicare for All bills introduced by Senator Bernie Sanders and by Representative Pramila Jayapal would expand coverage to virtually everyone in the U.S., including undocumented immigrants. Some leading Democrats prefer a more measured approach, similar to Hillary Clinton’s 2016 healthcare reform proposal, which included a provision similar to California’s subsequently withdrawn 1332 waiver proposal. (It would have allowed undocumented immigrants to buy coverage in the exchanges, although without subsidies.) Joe Biden’s health care plan includes a similar proposal, which would allow undocumented immigrants to buy into a new public option program, albeit without any government subsidies.

But over the first seven years of exchange operation, roughly 85 percent of exchange enrollees have been eligible for subsidies, and only 15 percent have paid full price for their coverage. So although public option plans are expected to be a little less expensive than private plans, it’s unclear how many undocumented immigrants would or could actually enroll in public option without financial assistance.

Harold Pollack has noted that our current policy of entirely excluding undocumented immigrants from the exchanges is “morally unacceptable.” As Pollack explains, Clinton’s plan (and now Biden’s plan) to extend coverage to undocumented immigrants by allowing them to buy unsubsidized coverage in the exchange is a good first step, but it must be followed with comprehensive immigration reform to “bring de facto Americans out of the shadows into full citizenship.”

Louise Norris is an individual health insurance broker who has been writing about health insurance and health reform since 2006. She has written dozens of opinions and educational pieces about the Affordable Care Act for healthinsurance.org. Her state health exchange updates are regularly cited by media who cover health reform and by other health insurance experts.

The post How immigrants can obtain health coverage appeared first on healthinsurance.org.